Figure 1. COP displays range from small-format screens with a single display type to a wall ofscreens with multiple, simultaneous displays.

Recognizing these needs, the industry has created reusable best practices for a common operating picture(COP) for incident response that is supported by open standards. The tools for implementing this COP, including functionality for collecting and displaying all relevant live video and data, have been maturing over the years and are now available to provide real-time feedback as well as replay capabilities for detailed analysis and continuous improvement processes. With proper planning and implementation,a COP can be deployed quickly in any region of the globe to provide a comprehensive tactical operational view, whether for incident response or to enhance daily operations.

Lessons Learned

The April 2010 Macondo/Deepwater Horizon incident in the Gulf of Mexico and the earlier Montara oil spill in Australia drew worldwide attention to the need for a standards-based response management COP. In the case of the Deepwater Horizon incident, there were numerous barriers to any sort of synchronized, total domain awareness. These included lack of consensus over what data should be tracked and transmitted, inadequate tools for pushing real-time data throughout the response organization, and a lack of interoperable communications technology.

To identify learning opportunities following the Deepwater Horizon and Montara incidents, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (OGP) formed the Global Industry Response Group (GIRG), which delivered 19 recommendations to pursue, as part of a 3-year Oil Spill Response Joint Industry Project (OSR JIP). Today, a number of these OSR JIP projects are underway, including two related to COP development — one for GIS/mapping of an oil spill response and the second for using GIS technology and geo-information in a response management COP.

According to the OGP, a COP “..is a computing platform based on Geographical Information System (GIS) technology that provides a single source of data and information for situational awareness, coordination, communication and data archival to support emergency management and response personnel and other stakeholders involved in or affected byan incident.” A common solution is to utilize ArcGIS Online (AGO), as this platform allows for quick visualization and representation of the field of operations, rapid deployment of the various GIS feature sets, and the ability to transform the core data to OGP standards.

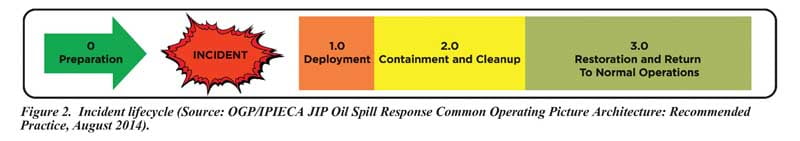

A COP may be implemented for many types of oil spill events, such as those involving on-land release, a coastal terminal or a tanker in transit, or offshore incidents related to platforms, pipelines, or a deepwater well blowout. The COP should accommodate each step of the incident lifecycle, as shown in Figure 2, which requires proper planning atthe beginning of any oil spill response. A comprehensive planning process using a standardized template will establish the foundation for response-related information management and data sharing using agreed-upon data standards,field reporting requirements, media formats, and data archiving procedures.

The COP will be used in different ways by different stakeholders in a typical response operation. For instance, the command team will use it to conduct the daily briefing sand as a dashboard for reporting and analysis. The planning group will use it to communicate with other response teams for purposes such as in-situ burns, boom deployments, skimming operations, and beach cleanup. The operations team will use the COP to communicate with the field team about activity status, ensuring they all share the same real-time location information about task forces, major vessels, and current and predicted weather data. The COP will also be used by the legal team for long-term litigation support and can be an important tool for public stakeholders as well, including the general public, news agencies, and academic institutions.

The operational and emergency response teams are responsible for selecting and distributing COP information to other parties through a controlled release to sites including offshore platforms, drill ships, remote underwater vehicles (i.e., ROVs), docks, support vessels, and onshore field sites. This information is gathered and transmitted via satellite systems or land-based Internet circuits. In order to function effectively, a COP must visually show all of this information within the area of responsibility (AOR)in real or near-real time and provide a dashboard for reporting and analysis.

Establishing the Right Framework

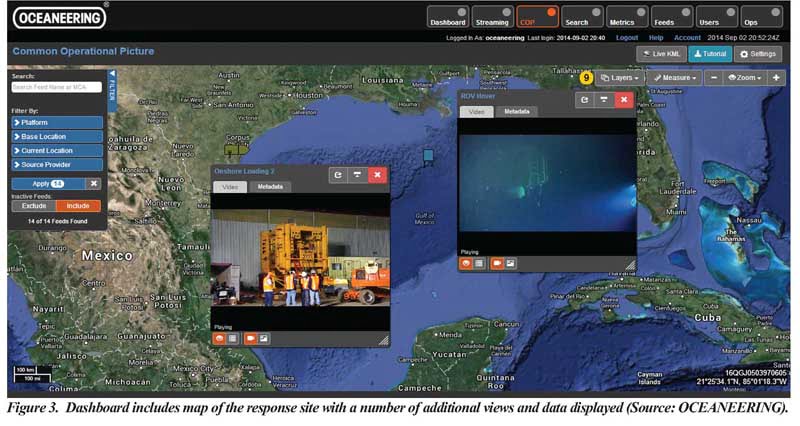

The best approach for deploying a COP is to use a portal-based architecture, which has proven effective in past response activities. Additionally, the integration of interfaces by using a common database back-end allows a more flexible method of displaying all data. The structure of the COP dashboard is also particularly important, as users will rely on it to provide an at-a-glance summary of all COP information. Figure 3 provides one dashboard example.

COP data can include vessel positioning data, weather,sensor feeds, and various audio, video, and other data — all coming from a variety of sources using a variety of formats. Standards make it easier for disparate systems utilized during an incident to consume, analyze, display, and interact with this information. For this reason, the industry has established specifications for key COP elements including web map services, which dynamically produce spatially referenced maps portraying geographic features for retrieval by the user client dashboard, and for servers that are used for geographic features and coverages.

Other information technology tools and systems used by incident command are evolving to include basic COP functionality as well. These tools and systems support processes ranging from procurement to internal and external communications, asset management, invoicing, claims, and reporting. Their integration with the COP helps facilitate data flow and simplify information management processes, so they, too, must be based on open standards.

In the case of proprietary data, it should be integrated into the COP using appropriate levels of data security. The recommended approach is for all providers of any particular data set to make their information available via an open-standard model that can support security requirements and compatibility.

Finally, the COP solution should also meet all regulatory, legal, and other requirements and minimize liability and exposure during an event while also providing ongoing benefits during normal operations.

Video and Other Inputs

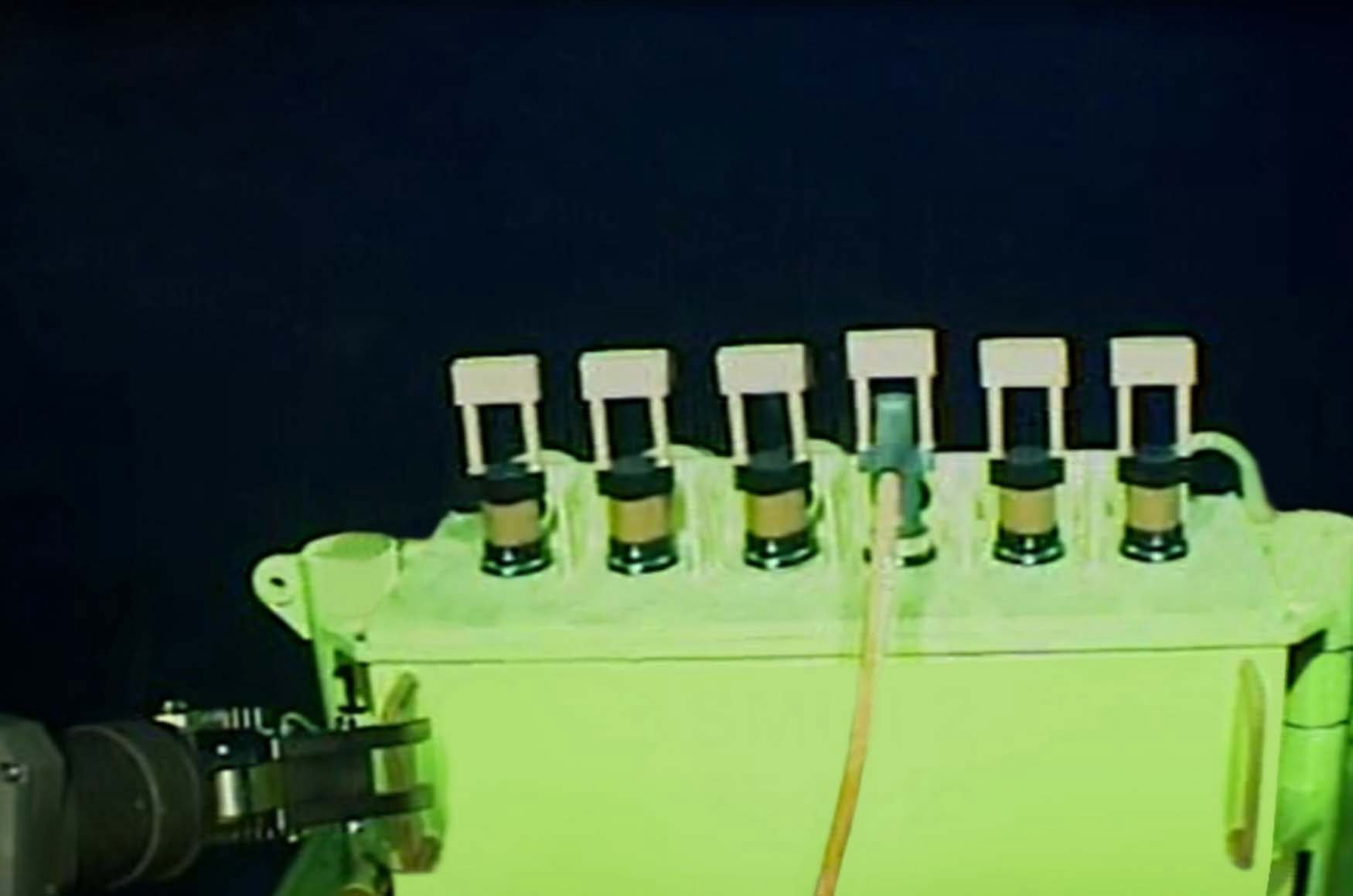

For daily operations and incident response, video and telemetry data capture is an increasingly important requirement. Video images, in particular, can provide unique realtime and historical awareness of the incident (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The video portal access can provide various views of the video and telemetry feeds coming in from the remote location.

Like other COP data types, video is delivered using web services and encodings that support open standards. The COP user interface and web services provide functions such as viewing controls (play, pause, etc.), video library queries (including search by keyword and tags), and video stream selection. Provisions also should be made for cataloging and handling video data, securely transferring hard drive media from offshore to onshore, professional video editing and annotation, and video archiving. The interface between an Incident Command Center and COP clients should be based on Motion Imagery Standards Board (MISB) specifications, in support of multiple formats.

One other more recent input to consider is social media monitoring, which can inform oil spill response, particularly if the spill is in an area close to people. Attention must be paid to monitoring, filtering, and confirming social media reports as part of including them in the COP.

A coordinated approach to offshore communications has become increasingly important for both daily operations as well as incident response. This has led to the development of industry standards for a universal COP that can be used for gathering, collating, synthesizing, and disseminating incident information to all appropriate parties involved in an incident. Tools for implementing a COP based on these standards are now available, and their adoption is growing, worldwide, in applications where there is the need to collect, display, and share a wide variety of data — including live video — between multiple stakeholders in demanding onshore and offshore environments.

For more information visit www.oceaneering.com.